Yamada Kõun Rõshi was the main teacher of Pia Gyger and Niklaus Brantschen SJ until his death. As head of the Sanbo Kyodan group, he carried on the legacy as the Dharma successor to his teacher, Yasutani Haku’un Ryoko.

Zur Vitae von Yamada Kõun Rõshi (Zendo Stäfa) in German

Vitae of Yamada Kõun Rõshi (Ruben L. F. Habito, Original university press Hawaii)

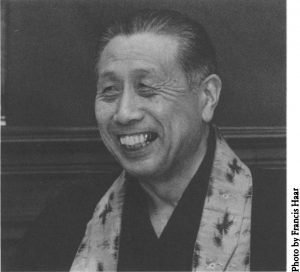

In Memoriam: Yamada Kõun Rõshi (1907-1989)

NO LONGER BUDDHIST NOR CHRISTIAN.

Author: Ruben L.F.Habito Source: Buddhist-Christian Studies, Vol. 10 (1990), pp. 231-237 published by: University of Hawai’i Press; Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1390209 accessed: 15/12/2019

Yamada Kõun Rõshi (1907-1989)

In 1970 Yamada Kôun Rôshi became head of the Sanbô-Kyôdan (Order of the Three Treasures having succeeded Yasutani Hakuun, who had designated him official Dharma Successor many years earlier. At that time the Zen meditation hail established at the lot adjacent to his modest home, called San-un Zendõ or the Zen Hall of the Three Clouds, was becoming an active Zen center where Japanese and non-Japanese congregated regularly to do zazen (sitting Zen meditation), listen to teishõ (exhortatory talks given by the Zen Master to practitioners), and receive dokusan (individual interviews with the Master).

My own first encounter with Zen was not until the spring of 1971, at Engakuji, a Rinzai monastery where D. T. Suzuki had trained. Soon afterward I was introduced to the San-un Zendo by Father Thomas Hand, S. J., my spiritual director at the Jesuit language school where I was staying and learning Japanese language and culture. Father Hand was himself a regular “sitter”~ and disciple of Yamada Rõshi.

This Zen Hall progressively became a spiritual center for men and women of a wide range of origins, interest, and even religious affiliations. It was held together as a community by the dynamic and winning personality of our Zen Master, Yamada Koun Roshi, assisted by his vivacious and solicitous wife, in whom especially the non-Japanese found a true mother away from home, and whom we all endearingly called Okusama (the Japanese term for “Mrs.”, but literally, “the venerable one inside the house”).

This small Zen community based in a little corner of the scenic and historic city of Kamakura continued to prosper, and its reputation gradually spread beyond Japan through all parts of the globe, enticing scores of earnest seekers from across the seas to come and stay either on a long-term basis or periodically, especially during the summer months, in order to be close to the R6shi and to be able to participate in the regular sesshin or Zen retreats held five or six times during the year.

This Zen community actually traces its roots to the initiative of Zen Master Harada Sogaku (Dai-un or Great Cloud), who, though a Soto monk, was dissatisfied with the state of Soto Zen during his time, and went over for k6an training with Rinzai Masters. Based on his insider’s experience of the best of the two Zen schools, Harada Rõshi then organized a rigorous training program for his disciples consisting of six to seven hundred kõan. He handed this practice down to his Dharma Successor, Yasutani Hankuun (White Cloud), who refined it and passed it on to Yamada Kõun (Cultivator of Clouds).

This training program begins with an intense initial period that gears the seeker toward a genuine experience of realization (called kensho or “seeing into one’s own nature”). Yamada Roshi’s special charisma was his magnetic way of directing each seeker, especially in the initial stages, toward the fundamental and decisive kensho experience. However, what he brought to bear on every koan in the post-kensho stages also testified to the breadth and depth of his Zen vision. I remember instances of going through particular koan with him wherein he would say, “Harada Rõshi understood it this way. Yasutani Rõshi saw it this way. I would do it this way,” thus opening up new treasures for the practitioner.

The impact of Yamada Rõshi’s Zen life and teaching on the rest of the world is beginning to make itself felt, as the disciples whom he personally trained, during his two decades of active directorship of San-un Zendo, take upon themselves the task of directing their own Zen groups in different parts of the globe. Some of these new groups are already thriving Zen communities in their respective areas, such as those directed by Robert Aitken, Roshi in Hawaii, and the various groups under Yamada R6shi’s European disciples beginning with Brigitte D’Ortschy Roshi and others.

After his passing on September 13, 1989, a document was found among his files with a list of the Zen names that he himself gave to his non-Japanese disciples who had finished the koan training under his direction. The third character found in each name is either ken, meaning “house” or “lineage,” or an, meaning “hermitage,” the former accorded to men, the latter to women. The list is as follows:

U.S.A.

Aitken, Robert-Gyo-un Ken (Dawn-Cloud)

Habito, Ruben-Kei-un Ken (Grace-Cloud)

CANADA

Stone, Roselyn-Sei-un An (Clear Cloud)

INDIA

Samy, AMA-Gen-un Ken (Dark Cloud)

PHILIPPINES

MacInnes, Elaine-Ko-un An (Shining Cloud)

Golez, Mila-Gyoku-un An (Jewel Cloud)

Punzalan, Sonia-Shia-ni An (Essence Sister)

EUROPE

Brantschen, Niklaus-Go-un Ken (Enlightenment Cloud)

Fabian, Ludwigis; Ko Un An (Wolke des Wohlgeruchs)

Jager, Willigis-Ko-un Ken (Empty Cloud)

Kern, Heidi-Heki-un An (Blue Cloud)

Kopp, Johannes-H6-un Ken (Dharma Cloud)

Lassalle, Hugo-Ai-un Ken (Love Cloud)

Lengsfeld, Peter-Ch6-un Ken (Highest Cloud)

Low, Victor-Yui-un Ken (Eternal Cloud)

Meyer, Gundula-Zui-un An (Felicitous Cloud)

D’Ortschy, Brigitte-Ko-un An (Shining Cloud)

Rieck, Joan-Jo-un An (Pure Cloud)

Schlütter, Ana Maria-Ki-un An (Radiant Cloud)

JAPAN

Reiley, Kathleen-Sei-un An (Immaculate Cloud)

Shepherd, Paul-Cho-un Ken (Transparent Cloud)

Loy, David-Tetsu-un Ken (Wisdom Cloud)

This is only a partial list, and does not include the many Japanese practitioners who have finished koan practice in the existing sister Zen groups in Kyushu, Osaka, Tokyo, Hokkaido, and so on. . Many of the Japanese who have finished now serve as elders in the Kamakura Zen community, helping out in the introductory talks, and management of sitting sessions and retreats.

Unfortunately Yamada Koun Roshi was not able to make public before his death his own choice of who would be his main Dharma Successor from among the many disciples he had seen through the long rigorous training program, and so the Board of Directors of the Sanbo-Kyodan decided to name Kubota (Akira) Ji’un, Roshi, as the new head of the group. He had also received training under Yasutani Roshi and had been helping to give direction to the Kamakura San-un Zendo since the late 1960s. He will be assisted by Yamada (Masamichi) Ryoun, son of the late Yamada Roshi.

Looking back at the nearly two decades of work with Yamada Koun, R6shi, I note three points which can be regarded as his unique and distinct contribution as a Zen master. The first point is what we can term the “laicization” of Zen, that is, breaking the wall between “monastic” and “lay” in Zen life and discipline. In contrast with his predecessors Harada and Yasutani, Yamada Roshi himself was never a Zen monk nor a temple priest (although it is said that he had received Buddhist preliminary ordination). He was primarily a man wellversed in worldly affairs, in business, in legal matters, and in medical administration, and was the father of a family with grown-up children

Up to the time of his illness he was Director of the Kenbikyo-in, a clinic and Public Health Facility in Tokyo whose main function was the diagnosis of outpatients, and Mrs. (Kazue) Yamada is its medical director. He commuted daily from his residence in Kamakura with the thousands of Japanese commuters from the surrounding areas. He was also generous with his time in his office to receive some of his disciples in dokusarn even during ordinary days of the week. (Foremost among these dokusan clients for many years was Father Hugo Enomiya Lassalle, SJ., assiduous in his Kõan studies even as he approached the age of ninety.)

The Zen community that grew and developed under his direction was also primarily a lay community, though there were some Buddhist monks and temple priests among the members. Although there were many Catholic priests and sisters and Protestant pastors among the non-Japanese, there was a pervasive spirit of lay practice in his center. The significance of this cannot be overestimated. In the history of Buddhism, lay persons have always been regarded as “second-class citizens,” while those who have renounced worldly life and lived the monastic life have been regarded as ones on the direct path toward the goal of enlightenment. To a great extent this monastic flavor predominates in the image of Zen transmitted to the Western world.

Yamada R6shi’s entire life and teaching as a Zen Master, however, as well as the Zen community that received nourishment from his life and teaching, dissolved the distinctions between “monastic” and “lay,” or further, between “religious” and “secular”. In his talks, Yamada R6shi would frequently refer to “Yuima-koji” or “the lay person Vimalakirti,” central character in the Vimalakfrti-nirde&a Sgtra, who as a lay person embodied the highest attainment of Buddhist enlightenment, winning over and becoming the teacher of monastic disciples. Yamada Roshi made it clear that the central function of Zen is to break through such distinctions and embody the highest attainment of enlightenment in the ordinary events of human life.

This is also what lay behind Yamada Roshi’s frequent insistence that the truly accomplished Zen person is the one who has thrown out every bit of self-consciousness about enlightenment itself, and is simply back to living life in its ordinariness, with one significant difference: that the ego no longer comes to the fore to mar the tasks. Thus he intended that the long and rigorous process of kooan study should accomplish the whittling down of that ego to its original nothingness.

The second point to be noted in Yamada Roshi’s Zen life and teaching was concern with the social dimension of human existence. This he regarded as the outflow coming from the wisdom of enlightenment-of seeing the nature of things as they really are in their emptiness and mutual interconnectedness. Compassion is grounded in realizing oneness with all living beings, in all their joys and hopes, in all their sorrows and pains. In his teisho as well as in his opening comments in Kyosho (Dawn Bell), the bi-monthly journal of the Sanbo-Kyodan, he discussed not only specific Zen topics, but also frequently referred to political, economic, and social issues, voicing his concern about poverty and a militarized globe – alling upon world leaders to take more seriously their tasks of peace. He sometimes spoke of the impossible dream of getting these world leaders together in a “Zen summit” to tackle together the crucial problems confronting humankind based on a Zen process of self-emptying.

But Yamada R6shi’s Zen life is going to make its impact on the rest of the world most probably for his third contribution to world culture: : he was able to break the traditional sectarian barriers that separated Buddhists and Christians, encouraging the rise of a Zen community composed of both devout Buddhists and equally devout and practicing Christians. In the list of those who have completed k6a,n training and have been given Zen names, the majority are Christian priests and nuns. This calls for a reordering of our stereotyped notions of Zen, of Buddhism, of Christianity.

Reverend WilligisJager, O.S.B. (Ko-un Ken), who had spent many years in Zen training under Yamada R6shi in Kamakura and now directs Zen groups in Germany, commented at the 1987 International Buddhist Christian Conference held at Berkeley, with Yamada R6shi himself present in the panel as one of the keynote speakers: “Many can argue whether a Christian can validly do Zen or teach Zen, or not. The fact is, I am doing it.”

I recall that this was a point of contention when I began to receive direction under Yamada Rõshi almost two decades ago. At that time there were several Catholic sisters and priests who were avid disciples sitting regularly at San-un Zendo, but not one had passed through the initial barrier of the kensho experience. In the introductory talks initiating me into discipleship (called sosan no hanashi, or talks to be heard by all), one of the assistants giving the talk looked at me from the corner of his eye (at the time I was aJesuit seminarian studying for the priesthood) and referred to Christians as doing gedo or “outside the way” Zen,. which meant that they were not doing it in the proper way.

This was a view expressed also by Yasutani R6shi, who often criticized Christians for their attachment to the concept of God as an obstacle in attainment of enlightenment. He urged them to cast away this concept if they really meant to practice genuine Zen. The disciples who came to Yasutani Roshi were advised to follow the Buddhist way and urged to take the precepts, if they were to pursue the genuine path of Zen.

But Yamada R6shi received the Christians as they were, without requiring them to change their religious status, but he was as emphatic nevertheless about non-attachment to ideas or concepts and stressed that Zen is not a philosophy or school of thought, but a way of pure experience, independent of mental concepts. s. Given the proper guidance, a person assiduous in practice could be led to that pure and genuine Zen experience, whether that person were a professed Buddhist Christian, or what. He stressed the point that Zen practice makes the Buddhist more fully a Buddhist, and suggested that the Christian could be a better Christian by living the Zen life.

This assurance and encouragement from the Rõshi bore its fruit, and one after another, his disciples who were practicing Christians were confirmed in their kensho experience. And in the post-kenshõ kõan training, there was no distinction made in the religious affiliation of the practitioner Yamada Rõshi termed this part of the practice as the process of “washing away” the remaining bits of the ego and of polishing away the sheen and glitter of the enlightenment experience to enable the practitioner to be more fully rooted in the ordinariness of life. e. In this aspect there was no longer any distinction of Buddhist or Christian, male or female, young or old, but simply the encounter with bare facts of human experience that every koan would highlight in a very particular and concrete way. In my own personal case, entry into the world of Zen after the initial kensho experience threw fresh light on my reading of texts of Christian scripture, leading me to a new and living encounter with these texts.

At regular sesshin at San-un Zendo, at least a fourth of the fifty or so participants would be practicing Christians. We were allowed to have a Eucharistic celebration in a separate room while the Buddhists were in the main hall reciting the morning sutras. It was in these very intimate Eucharistic celebrations during sesshin that Christian liturgical expressions came alive with cosmic, and at the same time quite concrete, significance.

I myself personally made it a point to communicate to Yamada R6shi, by letter and by direct conversation, the newer and newer vistas I was receiving in my understanding of the Christian mystery in the light of my Zen experience, e, and it was likewise a joy to me that he himself gradually became more and more appreciative of those dimensions of the Christian religious tradition that somehow reverberated themes in the world of Zen, and he took up some of these themes in his own teisho now and then.

Yamada Rõshi’s Zen life and teaching, in short, was simply a bringing to its full implications the key principle in Zen of “no reliance on words or concepts,” which means that it is a call to a constant return to the fundamental Zen experience, the experience of the world of emptiness (“karappo no sekai” as he would frequently repeat in Japanese, even while he was on his sick-bed in the months preceding his passing). In this world of emptiness there is no longer Buddhist nor Christian, but simply, “Have you eaten?” “Yes, sir.” “Then wash your bowls!”

Ruben L. F. Habito, Perkins School of Theology, Southern Methodist University